The early voyagers for pleasure on our waterways seem to have been an invariably shy and retiring bunch of individuals whose descriptions of their travels were more often than not written anonymously. Of the five earliest books describing canal voyages for pleasure in the UK no less than three were written under a non de plume and I have often wondered why. Respectability – was one of the keystones of the Victorian middle classes and so to deviate into anything as obscure as canoeing on canals and generally messing about in boats portrayed a possible character flaw not to be advertised. My theory anyway.

The very earliest of these books - ‘A Trip Through the Caledonian Canal’’ seems to have taken place in 1861 and was published the same year by the anonymous author - ‘Bumps’. A few years later and after the formation of the Royal Canoe Club by the indefatigable John MacGregor whose exploits on canoeing Continental waterways (He seems not to have bothered with UK waterways other than the Thames) excited the middle class public of the time leading to Royalty ,Charles Dickens & Robert Louis Stevenson amongst others taking up the new sport of ‘Paddling’; –another book was published, again anonymously, – ‘The Waterway to London as explored in the ‘Wanderer & Ranger with sail,paddle & oar in a voyage on the Mersey , Perry, Severn & Thames and several canals’ –1869. (This book is the subject of an excellent article by Richard Fairhurst in the current edition of Waterways World ).

Both the two books so far mentioned are illustrated and we are indebted to Canal historians and book collectors whose researches, have in the last few years ascertained the true identities of both authors.

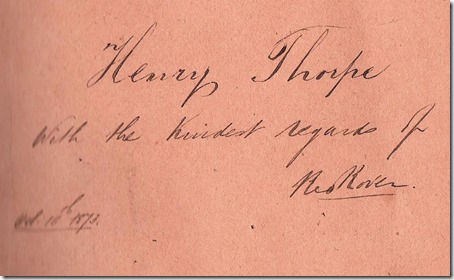

I wish I could say the same for the third of these early anonymously authored books. ‘Canal and River – A canoe cruise from Leicestershire to Greenhithe’ -1873. The author who hides his identity under the nom de plume of ‘Red Rover’ has still, 150 years, later to be identified. Indeed in my presentation copy to a friend the author still refers to himself as ‘Red Rover’

Any Canal book collector who has tried to find one of these books will know how elusive they can be. This is of course due not only to the 150 years + age of the books but also because some of them were published privately in very limited numbers for family and friends and went only through the one (First) edition and were never reprinted.

Any Canal book collector who has tried to find one of these books will know how elusive they can be. This is of course due not only to the 150 years + age of the books but also because some of them were published privately in very limited numbers for family and friends and went only through the one (First) edition and were never reprinted.All is not lost however for most of these books can be seen in many of the Universities libraries and facsimile copies of some of them have been issued by the British Library under its Historical Prints label. Most keen collectors use Copac which is a general site which shows all the British University libraries and The British library and here you can search for any book and find which institution has a copy.

However returning to Red Rover - I think it must be just about the rarest UK canal book you could ever try to find. Again, searching in Copac – none of the Universities seem to have a copy and amazingly even the British Library doesn’t list it . It is, interestingly, printed by a provincial publisher in Bedford and that may partly explain its scarcity. In over 40 years of collecting I have never seen a copy for sale and it was indeed my lucky day when I obtained a copy at auction and this copy had previously been in the collection of Charles Hadfield.

However returning to Red Rover - I think it must be just about the rarest UK canal book you could ever try to find. Again, searching in Copac – none of the Universities seem to have a copy and amazingly even the British Library doesn’t list it . It is, interestingly, printed by a provincial publisher in Bedford and that may partly explain its scarcity. In over 40 years of collecting I have never seen a copy for sale and it was indeed my lucky day when I obtained a copy at auction and this copy had previously been in the collection of Charles Hadfield.THE BOOK. …………………………………………………

Thursday the 22nd August 1872 saw Red Rover at Bedford station attempting to fit his canoe into the guards van of a train bound for Market Harborough a few mile up the line. As it was too long for the van it was, amazingly, strapped to the roof instead. On arrival at the canal basin the author objects to the 5 shilling toll demanded, whereupon an alternative fee of four pence per ton for a minimum of 6tons is agreed upon and so at the end of chapter 1 we see our author paddling his rather heavy (on paper) canoe towards Foxton 6 miles away.

He seems to have found the arm to Foxton very overgrown and seemingly seldom used and indeed he remarks that he only passed three boats between Foxton & Buckby.

A method of propulsion much favoured by early canoeists was the sail or sometimes two sails and our man, finding the wind right, uses this method for 8miles or so to Crick tunnel where he has to wait for a horse boat to exit.

One of the things that I like about this book are the authors interactions with the boat community and digressions and descriptions of village life en route. After a description of being towed behind 3 boats in Braunston tunnel by the steam tug, at Braunston he searches for somewhere to stay and gives a good description of the village shop & butcher who provides probably the worst pork he has ever tasted. He hears an early Trade Union song in a nearby pub. On the Oxford Summit he is stared at uncomprehendingly by gleaners in the canalside fields and remarks on the comments made by the women and the silence of the men.

At Banbury he transfers to the Cherwell but finds it very overgrown until at Twyford a rain soaked author is dried out & fed by the miller who assists him with a ‘flush’. The struggle through an overgrown Cherwell finally prompts him to return to the navigation at Kings Sutton where he overtakes a horse drawn pair. One of these the ‘Mary Ann’ offers to dry him out & give him shelter and a bed for the night. There then follows one of the best descriptions of the boaters and their life that I have from this time whose authors sometimes view the Canal workers as if from another planet. He remarks on the cleanliness of the boat with its unbleached calico sheets and straw paillasse. The painted decoration and polished brasswork is admired especially since the captain is a single 35 year old male. Red Rover states that the other boat was captained by a 35 year old man,his wife and small child.

They cast off from an overnight mooring at 2am and the author joins in the steering and lock work etc before re-joining the Cherwell at Enslow on his way to Oxford,the Thames and London .

A small unillustrated book and only 90 pages long but invaluable for its description of an early voyage on a canal and especially for the authors reactions to the Canal Boat people he came across whom he found to be universally helpful and to lead clean industrious but hard lives. He makes a point of these last traits because in some ‘educated’ quarters at that time - canal boat life was portrayed as squalid, drunken and immoral.

N.B - Checking the Canal Boat Inspectors records from Lower Heyford on the Oxford Canal

- the first record for a boat named the 'Mary Ann' occurs in 1893 which is sometime after the events narrated in the book. This boat was inspected on 27th May 1893. The Reg No was 17a and the boat was first registered at Banbury on the 24th Feb 1879 in accordance with the new Canal Boat Act of 1877 .The owner & captain is given as William Humphris Jun of Thrupp.

On the same day the 'Caroline' was inspected.This boat Reg No 18a was registered at Banbury on the same day as the 'Mary Ann' in 1879 and also belonged to William Humphris.

What is interesting is that in succeeding years these two boats were often inspected when passing through Lower Heyford together. It is this fact that makes me wonder if these two boats towed by the one horse are the boats mentioned in the book.

Its only a conjecture of course. Mary Ann is a common name and Humphris is a family name that occurs many times in the records and has innumerable connections with Thrupp, Eynsham & Oxford. Its good to record that the family probably prospered as they seem to have purchased another boat the 'Nettle' which was first registered at Oxford in 1886.

It seems too that the single male captain had during the years since meeting Red Rover in 1872, married and produced the usual large family, since the records show that since that time Harriet 3, Rose 1, John 5 had arrived. The married couple on the other boat had Annie 15 and Clara 14.